Have you ever been in a situation where you’ve looked at a workout on your program for the day and a little voice inside chimes in telling you that your body is just not up for it? It could be that you’re feeling slightly under-the-weather, or that you have a niggle that is complaining a bit more than usual, or you’re feeling a higher level of fatigue that day. Do you listen to this gut feeling and sit out, or do you rationalise with arguments of ‘pushing through’, thinking the coach knows best, not wanting to seem lazy, or having an unassuageable desire to tick the box (i.e. see it go green in Trainingpeaks) just because the workout is there?

Part of being an (endurance) athlete is learning how to push through discomfort. That might be the piercing sound of the alarm at 4am, or the burn of hydrogen ions building up at the end of a hard interval. When you learn to push your body to go beyond what feels comfortable, one of the unfortunate side effects can be that you stop listening to those signals suggesting impending damage. There is certainly no greater interruption to training than injury or illness.

I have found as a general culture in triathlon and running, certainly in Queensland, that ‘more training’, and driving oneself harder is often perceived as better. You are given a larger degree of kudos if you cycle 200km, or you punch out 8x 1k run intervals at 3.20pace, than if you do an easy recovery run, despite the overall importance of recovery to success. Someone cycled around Australia once, and then there is impetus to cycle around it twice to ‘better’ the feat. If you’ve completed an Ironman, then of course it’s on to Ultraman! In a world driven by strava kudos and comparison it becomes easy to ignore your internal queues for self-preservation, and to push the envelope farther than what is healthy.

It has been an interesting experiment for me this year using Strava. I had previously shunned the platform as a slippery slope to over-exertion, unnecessary comparison, and potential overtraining. I have actually been surprised to find many positives to its use including: keeping connected to those in your sporting circles that you might not see on a daily basis (especially during COVID iso), having a strange sense of (online) community and support, learning different cycling routes, training strategies, and generally gaining some appreciation for the struggles and triumphs in the lives of other athletes. Undoubtedly some of my concerns have also been realised, and it has taken some strength to resist the temptation of comparison. I have found that it is a good way of quashing your own intuition by trying to ‘better’ another athlete’s training performance on Strava, especially when their circumstances may be very different to yours.

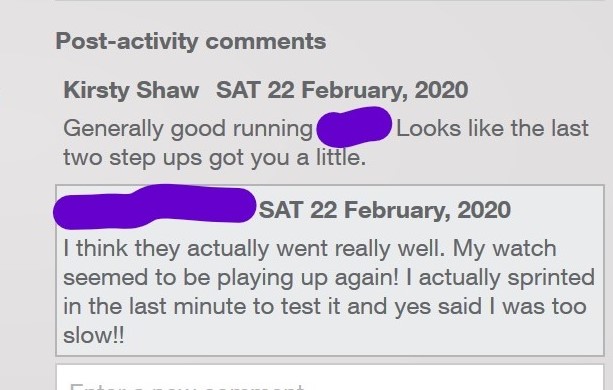

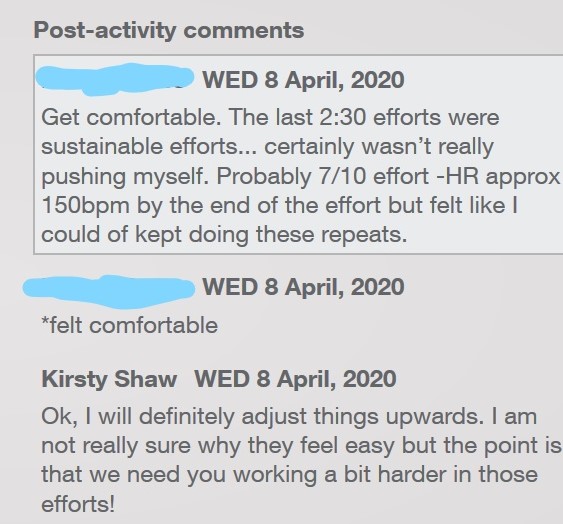

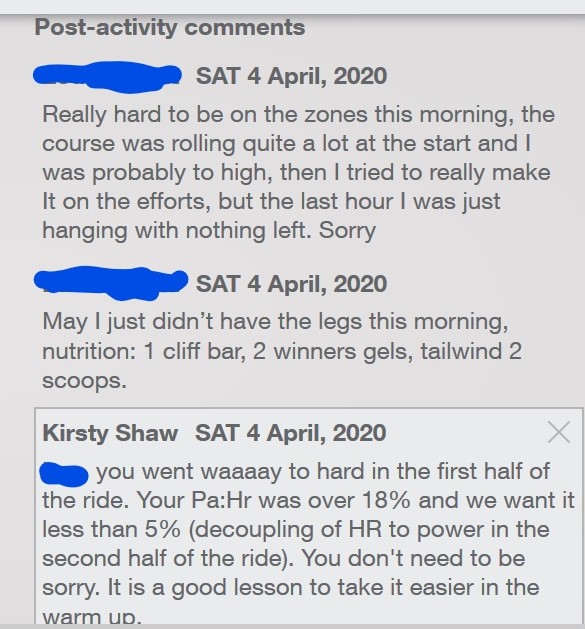

As a coach I look at overall periodisation of a program, and set this up according to key goals over the season. Whilst I try and account for other life stressors, health, age, gender, experience and the lifestyle of an athlete, it is impossible to adjust minutely depending on day-to-day changes in circumstance or ‘feeling’ that an athlete has. Trusting that your coach knows better than your intuition gives too much credence and power to their decision-making. Instead, I believe that it is important to be able to support the athlete in making the best choice regarding training, based on their immediate situation. For example; rather than blindly completing a high intensity set when you have a sore throat, and feel under-the-weather, the preference is that the athlete is supported to either have the autonomy to dial the set down, sit it out, or in the very least consult with me on how to adapt training.

Triathlon is rife with “exercise addicts”. There is a fairly strict set of criteria set out in the American Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders for differentiation of exercise addiction, separating this from a general, healthy love of training and involvement in triathlon. The criteria that always sticks in my head to help separate the two is: Continuance: continuing to exercise despite knowing that this activity is creating or exacerbating physical, psychological, and/or interpersonal problems. For me this is the ultimate ignorance of intuition; feeling that you are doing damage to yourself by training but being unable to resist completing the session. I think that many of us have been there before when you just know that you have some series signals telling you to lay off the training but you just can’t break the ‘consistent’ streak, or miss that session that suddenly seems paramount for your triathlon season. Converse to my concerns expressed about giving too much credence to your coach, this is a situation where the coaches’ stance can actually help to override the addiction. They can look at the situation objectively, and I believe, also have a duty to safeguard your health and wellbeing above all else. In these circumstances having an open relationship with your coach, and an immediate line of contact, can help support more intuitive training.

In theory as you become experienced in sports you should get better at making more intuitive decisions. You learn about yourself as an athlete and what you can and can’t tolerate. In practice I have actually found that greater experience can mean more reliance on deliberate decision-making rather than gut feel. Perhaps the thought process becomes more cognitive, and less spontaneous because it is not the first time the athlete has been in this situation. They ‘think’ back to what happened last time. They remember how much training it took to achieve the goal previously. They want to tick certain boxes that in the past created success, so they can feel confident. It seems that youth and ignorance can truly be bliss for helping you train to the tune of your own body!

My position when starting this blog was that the more intuitive you are able to be with your training, the better your chance of success. I was sure that I would find evidence to support that intuitive athletes have less injuries, ongoing illness, less missed training time, and therefore greater performance gains. Granted that my skills as a researcher may need to improve, I still submit that I found no such evidence. Much to my disappointment there seems to be a dearth of research on the subject. My “gut feel” remains that blocking out the externals, and listening to your body, is an essential part of ongoing success as an athlete.